Although I have not gotten much time in the saddle yet, I have spent a great deal of time this week working with the yearlings. I have never before worked with young horses and it is wonderful! There are 13 of them, all ranch bred, 9 of which are about one and the other 4 are two. The one year olds especially are very cute and very, very soft.

The first step to working with a yearling is actually catching it. This is much harder than it might seem since it is essentially feral and, though small, it is fast and hard-hoofed. We start by cutting a few out from the herd and herding them into a smaller pen. From there it is easier to separate one out and draft it into the round pen. Once in the round pen, the poor little guy usually panics and starts running around and around, scared to be alone and so close to a two legged carnivore who obviously intends to eat him. The first few times catching him is a battle, but it quickly gets easier once it has been handled a few times. They will often stop running, their eyes huge in their heads and their whole body shaking, as their brain battles their natural flight instincts. Once they face you, you can usually ease up to them and get a hand on them to get them caught.

The first moment of contact is transformative. Each time is like an epiphany in which the terrified creature suddenly realizes that they are NOT being devoured. After a few gentle strokes on the neck, they stop shaking, their breathing slows, and their eyes return to their sockets as they begin to relax. We rub them all over- on the face, neck, back, belly, and down the legs, until they stop flinching. We pull on their tails, fuss with their ears, and desensitize them to all manner of contact and stimuli. After a while they start to actually enjoy the experience. They will lean their heads into you searching for a scratch on the forehead, sniff at your hat, and sometimes their eyelids will flutter as they fight the urge to doze off. Once they understand what is being asked of them, they eventually allow you to lift their feet and to lead them around the arena.

This early process of desensitization is training not only for the horses but also for me and the other ringers. These young horses react to every movement you make. They are tuned into your energy and alert to your tone of voice. With older, well-trained horses, you can be fairly casual, even sloppy, but with these little guys you always have to be aware of yourself. Inevitably the horse you are working on will at some point bolt in surprise, so you have to be careful where you stand and how you hold them, both to be safe and to quickly regain control of the learning experience. If you are intimidated, you will teach your horse to be intimidated, but if you are too aggressive you will scare him. This activity forces you to be calm, assertive but gentle, and alert, all of which trains a good horseman as much as it does a good horse.

Saturday, March 20, 2010

Horsing Around (at last!)

This week we started working with the horses. HOORAY! I cannot effectively convey just how happy this makes me. The first time we went out to the “yards,” it was like handing an alcoholic a drink. I was practically shaking, I was so excited.

On Monday, Cameron came out with us. Most days I work with four 18 year old guys; Jesse, Jack, Matt, and Sam. Jesse is a second year hand and grew up training horses, but the other 3, for the most part, have not ridden before. So our first day was spent going over the basics- tacking, riding, safety, etc. Although remedial, it was nice to have everything demonstrated because, as with every other aspect of life here, almost everything is just a little different.

The preferred breed of horse in Australia is called the Stock horse. It is similar to the American Quarter horse, except that it is generally taller and stouter. Walhallow raises its own horses and these tend to be Stock horses bred to a Thoroughbred stallion. They are good, solid looking horses, but I must admit, I am a lifelong sucker for the Quarter horse.

Unlike on American ranches where horses are ridden in Western saddles and trained Western style, both Australian tack and training is something of a hybrid between functional Western and classic English. The saddles used here are called Australian Stock saddles. They are very similar to the American Western saddle except they conspicuously lack a horn. They also tend to be lighter and have smaller fenders, or sometimes only stirrup leathers, which allows for better contact between the leg and the horse, more like in English. The obvious question raised by the missing horn is how do they rope? Well, they don’t. Apparently Australian cowboying is centered around calf wrestling and brute force rather than roping, although I have not yet seen this first hand. The rest of the tack is all a little different too- no breast collar, no flank cinch, and a plastic-y, English-style bridle, usually with a simple snaffle bit.

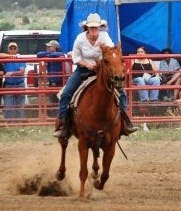

Because the station horses are still all turned out, we got to ride some of Cameron’s nice horses this week. I rode a beautifully trained, if slightly ornery mare named Arcadia. She was amazing. Although fat and out of shape, she responded both to neck reigning (Western) and leg yielding (English). She collected and extended like an English arena pony, but would instantly bear down and cut after a calf. I’m told that this is not the level of horse that I should expect, but boy was she fun to ride!

All told, I spent maybe 30 minutes in the saddle this week, and all of in the arena. But even that was enough to relight my enthusiasm for the work. After a morning spent with the horses, I can happily pick up my shovel and go back to stump digging, knowing that the next day would bring more horse time. Thank goodness!

On Monday, Cameron came out with us. Most days I work with four 18 year old guys; Jesse, Jack, Matt, and Sam. Jesse is a second year hand and grew up training horses, but the other 3, for the most part, have not ridden before. So our first day was spent going over the basics- tacking, riding, safety, etc. Although remedial, it was nice to have everything demonstrated because, as with every other aspect of life here, almost everything is just a little different.

The preferred breed of horse in Australia is called the Stock horse. It is similar to the American Quarter horse, except that it is generally taller and stouter. Walhallow raises its own horses and these tend to be Stock horses bred to a Thoroughbred stallion. They are good, solid looking horses, but I must admit, I am a lifelong sucker for the Quarter horse.

Unlike on American ranches where horses are ridden in Western saddles and trained Western style, both Australian tack and training is something of a hybrid between functional Western and classic English. The saddles used here are called Australian Stock saddles. They are very similar to the American Western saddle except they conspicuously lack a horn. They also tend to be lighter and have smaller fenders, or sometimes only stirrup leathers, which allows for better contact between the leg and the horse, more like in English. The obvious question raised by the missing horn is how do they rope? Well, they don’t. Apparently Australian cowboying is centered around calf wrestling and brute force rather than roping, although I have not yet seen this first hand. The rest of the tack is all a little different too- no breast collar, no flank cinch, and a plastic-y, English-style bridle, usually with a simple snaffle bit.

Because the station horses are still all turned out, we got to ride some of Cameron’s nice horses this week. I rode a beautifully trained, if slightly ornery mare named Arcadia. She was amazing. Although fat and out of shape, she responded both to neck reigning (Western) and leg yielding (English). She collected and extended like an English arena pony, but would instantly bear down and cut after a calf. I’m told that this is not the level of horse that I should expect, but boy was she fun to ride!

All told, I spent maybe 30 minutes in the saddle this week, and all of in the arena. But even that was enough to relight my enthusiasm for the work. After a morning spent with the horses, I can happily pick up my shovel and go back to stump digging, knowing that the next day would bring more horse time. Thank goodness!

Spinifax and Cattle Grids

It occurs to me that I have been entirely remiss is posting anything about what I’m actually DOING here. In truth, this was a somewhat intentional oversight because until this past week, the work so far has been a far cry from cattle work. As I have mentioned, it is still the Wet here, and although it only rained once last week, that was more than enough to keep the fields and many of the roads impassably soggy. So what does one do on a cattle station when you can’t get to the cattle? The answer? Manual labor. That’s right. Ditch digging, grass raking, truck fixing blue collar work. In particular there have been 2 tasks worth mentioning.

The first was harvesting spinifax. Spinifax is a sharp-edged bunch grass that grows in a manner similar to the tumbleweed (“rolly polly”) - big at the top, small and brittle at the roots, except that it doesn’t tumble. Because it grows in thick clumps, has a water repellent waxy cuticle, and grows like gangbusters all over the place, it is ideal for thatching roofs. Unlike in the US, where even the meanest structures are built with tin roofs, here they thatch the roofs at the cattle yards and round pens. This provides ample shade at lower cost and I’m told is actually much cooler. When it’s really hot out they will even set up a sprinkler on top of the spinifax roofs to provide a pleasant mist. All of this sounds lovely and comfortable, except that first you have to acquire the stuff. This entails sending 3 or 4 able bodied workers such as myself out to the side of the road to dig up truckloads full of the plants. It usually takes about 3 truckloads to thatch an old roof (double that if you’re starting from scratch), and the process of digging, loading, and thatching takes at least 3 hours per roof. Add to that the blazing heat, and the sharp, cutting blades of grass that make long sleeves, think jeans, and gloves essential, and you have the fixings for a very long day. It took us a whole week to thatch the roofs at the cattle yards, and I’ve heard talk of some new ones being built, but for now that’s done.

Last week the big project was digging out cattle guards (here called “grids”). For those of you who don’t know, a cattle guard is a grid made of railroad ties set over a ditch in the road. This allows trucks to pass over but keeps cattle out. However, on dirt roads like ours, the ditches underneath eventually fill with dirt, and that means that people like me get to go re dig them. That involves digging UNDER the grid- no easy task, and again, doing it in the blazing summer heat and full humidity. We dug out cattle grids all day long, all week long, and I thought I was going to boil alive it was so hot. Add to that foot-long centipedes and an assortment of snakes, toads, and lizards. “Experience Australia! Dig ditches in the Outback!” Right. Shockingly enough, this was not how they pitched the job to me 2 months ago. On the plus side though, I am in excellent shape.

Fortunately it has now (almost) officially stopped raining, so the the main event can begin. Soon enough I'm sure I will be up to my ears in cattle, working horseback or in the yards from before sunup to after sundown, 6 or seven days a week. As hard as that sounds, I can’t wait. I’ll tell you one thing though. I will not miss my shovel even for a minute.

The first was harvesting spinifax. Spinifax is a sharp-edged bunch grass that grows in a manner similar to the tumbleweed (“rolly polly”) - big at the top, small and brittle at the roots, except that it doesn’t tumble. Because it grows in thick clumps, has a water repellent waxy cuticle, and grows like gangbusters all over the place, it is ideal for thatching roofs. Unlike in the US, where even the meanest structures are built with tin roofs, here they thatch the roofs at the cattle yards and round pens. This provides ample shade at lower cost and I’m told is actually much cooler. When it’s really hot out they will even set up a sprinkler on top of the spinifax roofs to provide a pleasant mist. All of this sounds lovely and comfortable, except that first you have to acquire the stuff. This entails sending 3 or 4 able bodied workers such as myself out to the side of the road to dig up truckloads full of the plants. It usually takes about 3 truckloads to thatch an old roof (double that if you’re starting from scratch), and the process of digging, loading, and thatching takes at least 3 hours per roof. Add to that the blazing heat, and the sharp, cutting blades of grass that make long sleeves, think jeans, and gloves essential, and you have the fixings for a very long day. It took us a whole week to thatch the roofs at the cattle yards, and I’ve heard talk of some new ones being built, but for now that’s done.

Last week the big project was digging out cattle guards (here called “grids”). For those of you who don’t know, a cattle guard is a grid made of railroad ties set over a ditch in the road. This allows trucks to pass over but keeps cattle out. However, on dirt roads like ours, the ditches underneath eventually fill with dirt, and that means that people like me get to go re dig them. That involves digging UNDER the grid- no easy task, and again, doing it in the blazing summer heat and full humidity. We dug out cattle grids all day long, all week long, and I thought I was going to boil alive it was so hot. Add to that foot-long centipedes and an assortment of snakes, toads, and lizards. “Experience Australia! Dig ditches in the Outback!” Right. Shockingly enough, this was not how they pitched the job to me 2 months ago. On the plus side though, I am in excellent shape.

Fortunately it has now (almost) officially stopped raining, so the the main event can begin. Soon enough I'm sure I will be up to my ears in cattle, working horseback or in the yards from before sunup to after sundown, 6 or seven days a week. As hard as that sounds, I can’t wait. I’ll tell you one thing though. I will not miss my shovel even for a minute.

Speaking the Lingo

When I decided to take this job on the other side of the world, I breathed a sigh of relief because, obviously, Australians speak English. In the face of countless foreign experiences and situations, at least communication would not be a challenge the way it had been living in Belgium and France. Or so I thought.

In truth, Australian English and American English are related the way rock and roll and country music are related- both use the same basic components, but do so in a way that achieves entirely different results. My first week here I could only stare dumbly at people when they talked, barely able to extract even the vaguest meaning from their talk. Even now, conversations with me are strangled by “Sorry?”s and “What was that?”s and “I don’t know what that means”s. Thankfully the people here are, for the most part, very patient with me and have thus far been willing to repeat themselves ad nauseum until I understand. I keep telling myself that I just need time for my ear to adjust to this new version of my native tongue, but it’s slow going.

My trouble with Australian is threefold- the accent, the vocabulary, and the idioms. Combine these with some background noise and several people talking at once, and they may as well be speaking Dutch. The Australian accent that I have heard before is sort of a British southern lilt, exemplified by Heath Ledger, Nicole Kidman, and the like. However, the accent deep in the heart of the Outback is more like Australia’s version of an Alabaman accent- consonants and sometimes whole syllables go missing from words, parts of speech are dropped or mashed together, and sometimes it seems whole conversations can be had without any movement of the lips or tongue. One Sunday afternoon one of the women here asked “ch’bin kitchen’sm zeds?” I stared at her in astonished incomprehension and the poor woman had to repeat herself three times before I could decipher “have you been catching some zeds?” (ie- sleeping). Yes. Good talk.

The different accent is understandable- oceans tend to do that to the evolution of language. But the whole different set of words I find puzzling. For example, which linguistic evolution could have led to something being a “bell pepper” in the US but a “capsicum” over here? Why is a “wrench” a “spanner,” a “truck bed” a “tray,” and “ground beef” “mince”? Almost daily I pick up some object and say “What is this?” like some kind of very old kindergartener. Half the time the answer is “extension cord” and I am given a look that implies “What kind of idiot doesn’t know what an extension cord is?” The other half, the answer is some mysterious new term, like “conserve” (jelly) or “bonnet” (truck hood). Just to make things even more confusing, many of the words I do know don’t mean the same thing here. For example, cookies are “biscuits,” but biscuits are “scones” (pronounces Skohn, NOT skOne). Also, chips are chips or sometimes crisps, while fries are chips as well. Confusing.

To top it all off, almost everything Australians say is some form of colloquialism. For example, “hello” is “how ye goin’?,” "thanks" is "cheers," “you’re welcome” is ALWAYS “no worries,” and “OK” is “righteeo.” There are frequent references to “guts,” which means anything from "innards" to "middle" (of ANYTHING) or even "all of it." For example,you could say "The road runs through the guts of the paddock 9," but “you just add water and then stir the guts out of ‘er” is equally acceptable. Lovely. My favorite expression by far, though is “flash.” This means “cool” or “great.” In can be used as in “Oh, it’s nothing too flash” (here meaning “fancy”), or “That’s some flash new Ute you got there.” (“Ute” means any type of "utility vehicle," but most commonly refers to a car similar to the El Camino, popular among Australian males age 10-100. Of the 10 personal vehicles at the station, 7 of them are Utes.)

Given the amount of trouble I have had understanding them, the Australians say they can almost always understand me (almost). I probably have Hollywood to thank for that. There is a British fellow here, our full-time pilot, and while I can understand him easily, the Australians often don’t at all. Curious to see just how far this country has strayed from the Mother Land.

In truth, Australian English and American English are related the way rock and roll and country music are related- both use the same basic components, but do so in a way that achieves entirely different results. My first week here I could only stare dumbly at people when they talked, barely able to extract even the vaguest meaning from their talk. Even now, conversations with me are strangled by “Sorry?”s and “What was that?”s and “I don’t know what that means”s. Thankfully the people here are, for the most part, very patient with me and have thus far been willing to repeat themselves ad nauseum until I understand. I keep telling myself that I just need time for my ear to adjust to this new version of my native tongue, but it’s slow going.

My trouble with Australian is threefold- the accent, the vocabulary, and the idioms. Combine these with some background noise and several people talking at once, and they may as well be speaking Dutch. The Australian accent that I have heard before is sort of a British southern lilt, exemplified by Heath Ledger, Nicole Kidman, and the like. However, the accent deep in the heart of the Outback is more like Australia’s version of an Alabaman accent- consonants and sometimes whole syllables go missing from words, parts of speech are dropped or mashed together, and sometimes it seems whole conversations can be had without any movement of the lips or tongue. One Sunday afternoon one of the women here asked “ch’bin kitchen’sm zeds?” I stared at her in astonished incomprehension and the poor woman had to repeat herself three times before I could decipher “have you been catching some zeds?” (ie- sleeping). Yes. Good talk.

The different accent is understandable- oceans tend to do that to the evolution of language. But the whole different set of words I find puzzling. For example, which linguistic evolution could have led to something being a “bell pepper” in the US but a “capsicum” over here? Why is a “wrench” a “spanner,” a “truck bed” a “tray,” and “ground beef” “mince”? Almost daily I pick up some object and say “What is this?” like some kind of very old kindergartener. Half the time the answer is “extension cord” and I am given a look that implies “What kind of idiot doesn’t know what an extension cord is?” The other half, the answer is some mysterious new term, like “conserve” (jelly) or “bonnet” (truck hood). Just to make things even more confusing, many of the words I do know don’t mean the same thing here. For example, cookies are “biscuits,” but biscuits are “scones” (pronounces Skohn, NOT skOne). Also, chips are chips or sometimes crisps, while fries are chips as well. Confusing.

To top it all off, almost everything Australians say is some form of colloquialism. For example, “hello” is “how ye goin’?,” "thanks" is "cheers," “you’re welcome” is ALWAYS “no worries,” and “OK” is “righteeo.” There are frequent references to “guts,” which means anything from "innards" to "middle" (of ANYTHING) or even "all of it." For example,you could say "The road runs through the guts of the paddock 9," but “you just add water and then stir the guts out of ‘er” is equally acceptable. Lovely. My favorite expression by far, though is “flash.” This means “cool” or “great.” In can be used as in “Oh, it’s nothing too flash” (here meaning “fancy”), or “That’s some flash new Ute you got there.” (“Ute” means any type of "utility vehicle," but most commonly refers to a car similar to the El Camino, popular among Australian males age 10-100. Of the 10 personal vehicles at the station, 7 of them are Utes.)

Given the amount of trouble I have had understanding them, the Australians say they can almost always understand me (almost). I probably have Hollywood to thank for that. There is a British fellow here, our full-time pilot, and while I can understand him easily, the Australians often don’t at all. Curious to see just how far this country has strayed from the Mother Land.

Friday, March 5, 2010

Vehicles

For those of you who don’t know, in Australia they drive on the right side of the road. This is fairly nerve shaking at first as you watch the bus you’re in deliberately hurtle itself down the wrong side of the highway. But there’s more to it than that. In the airport in Darwin I felt like I was constantly pushing against the flow of pedestrian traffic, only to realize that of course I was, since we tend to walk on the same side that we drive. When your boss says “climb in, I’ll drive you over,” if you instinctively move to the right side of the vehicle, you seem a little presumptuous. Also, even after several years of driving a standard vehicle, it’s disorienting to try to shift with your left hand. At first I worried that even the pedals would be switched, but thankfully they are not. Even more disorienting is trying to gauge the spatial relationship between the vehicle you are driving and the gate you are attempting to pass through when you are sitting on the wrong side. Fortunately the only main road out here has only one lane and almost no traffic, and beyond that, it’s a whole world of red dirt roads, so hopefully this will be less of an issue than it would be in a more densely populated area.

Like ranchers the whole world over, Australians love their trucks. However, unlike in the US, where the Ford/Chevy/Dodge debate is a heated one, here there is only one kind of pickup – the Toyota. In fact, they don’t even call trucks “trucks,” they just call them “Toyotas” the way we call tissues “Kleenex.” They are smaller than their American counterparts and have a rugged look about them that would only ever be appropriate in the Outback or on the Savannah. They make you want to go on Safari. Toyotas have two gigantic spotlight-type headlights in the front attached to the brush guard (here call a “bull bar,” pronounced “boo bah”). My FAVORITE part of Australian vehicles, however, is the snorkel. It is exactly what it sounds like. It looks like a tiny smoke stack sticking out of the hood at the right corner of the “windscreen.” It’s function? To ventilate the engine when driving through water over 3 feet deep. Which begs the question- Can you even drive through water that’s over 3 feet deep, snorkel or otherwise? Given that that much water is typically accompanied by an equal amount of thick, slippery red mud, I remain skeptical.

However, if it’s possible to drive through, the Australians will try it. They drive as if they were born with the skill, and in fact that’s very near to the truth. On my first afternoon here, Felicity, the ranch matriarch, came to pick me up in a tiny, prehistoric Land Rover with her 2 children. The catch? Tom, age 10, was driving. He’s so short that they had to strap a block to the clutch so that he could reach it, but apparently he’s considered qualified. I was astonished. When I voiced this surprise I was informed by Lucy, age 8, that she could also drive but wasn’t quite strong enough to shift by herself yet. Wow. Makes me feel like I got a late start.

Like ranchers the whole world over, Australians love their trucks. However, unlike in the US, where the Ford/Chevy/Dodge debate is a heated one, here there is only one kind of pickup – the Toyota. In fact, they don’t even call trucks “trucks,” they just call them “Toyotas” the way we call tissues “Kleenex.” They are smaller than their American counterparts and have a rugged look about them that would only ever be appropriate in the Outback or on the Savannah. They make you want to go on Safari. Toyotas have two gigantic spotlight-type headlights in the front attached to the brush guard (here call a “bull bar,” pronounced “boo bah”). My FAVORITE part of Australian vehicles, however, is the snorkel. It is exactly what it sounds like. It looks like a tiny smoke stack sticking out of the hood at the right corner of the “windscreen.” It’s function? To ventilate the engine when driving through water over 3 feet deep. Which begs the question- Can you even drive through water that’s over 3 feet deep, snorkel or otherwise? Given that that much water is typically accompanied by an equal amount of thick, slippery red mud, I remain skeptical.

However, if it’s possible to drive through, the Australians will try it. They drive as if they were born with the skill, and in fact that’s very near to the truth. On my first afternoon here, Felicity, the ranch matriarch, came to pick me up in a tiny, prehistoric Land Rover with her 2 children. The catch? Tom, age 10, was driving. He’s so short that they had to strap a block to the clutch so that he could reach it, but apparently he’s considered qualified. I was astonished. When I voiced this surprise I was informed by Lucy, age 8, that she could also drive but wasn’t quite strong enough to shift by herself yet. Wow. Makes me feel like I got a late start.

Food

The food here is amazing! It’s not fancy, it’s relatively familiar, and boy is it good! There are 5 eating times (not quite meals) every day, making the kitchen an important hub of activity. It is a small building consisting mainly of a cooking area and an eating area, separated by a counter of sorts. There are other rooms, but I don’t know what they’re for, so they clearly don’t matter. The building is almost always hot and always smells incredible. It is presided over a 60-something woman named Kay, whose husband is the mechanic and whose son works cattle. Although she is nominally temporary until they get someone permanent, she works magic in that place.

Breakfast is at 6:00. While this seems unreasonably early, predawn is the only time of day when it’s not oppressively hot and humid, so early morning is actually the most productive time around here. Until we get a full time cook, breakfast is being handled by one of the Station hands, a large, strong man, aptly called Bull. The meal is a condensed version of the English fry, meaning fried eggs, grilled tomatoes, Canadian-ish bacon, and toast. Every once in a while spaghetti-on-toast makes an appearance. (It’s basically spaghetti-O’s on toast. Yuck.) There are other strange Australian breakfast habits, like baked beans on toast, or pancakes with ice cream and syrup. (I had this particular delicacy at the HiWay Inn. What a GREAT idea!) All of this is accompanied by hot tea, coffee or milo (“energy food drink” something like tasteless hot chocolate, if you can bear to drink anything hot.

The next meal of the day is called “Smoko,” which I believe is a derivative of the smoking break. It is every morning at 9:30 and is recognized as being every bit as legitimate a meal as any other. It usually involves a cup of tea or coffee and whatever baked good Kay came up with the day before. America, I think there is something to be learned here.

Lunch is from 12:30-1:30; a difficult adjustment when you expect it at noon on the dot. Kay puts out sandwich fixings, salad (no dressing, only mayo – very Belg), leftovers from last night, and something new each day.

Work generally wraps up around 5 (thus far) and then at 6:00 the Recreational Club opens. The Rec Club is a little concrete structure with a pool table, a flat screen, a bar and a back patio. Drinks can only be bought from 6-7 and no alcohol leaves the building. There are 2 well-stocked fridges full of sodas (which all seem to be referred to as “Cokes”), beer, and canned mixed drinks (which are only available on Fri & Sat). Only 1 brand of beer is carried; XXXX Gold and XXXX Bitter, a Queensland company, both varieties of which are terrible concoctions that the guys swear by. There is also an unusual assortment of chips and candy bars, including “Twisties,” “Freddo Frog Twins,” “Crunchies,” and “Raspberry Gummies.” My favorite aspect of Australian food is that instead of listing “calories” on the nutritional label, it informs you of the “energy” content – a far more positive spin on junk food.

Last but certainly never least, dinner starts at 7:00. Wow. We have had roast chicken, curry beef with rice, roast with squash, onions and potatoes, and best of all, meat pies, to name just a few. Everything is something very familiar, yet somehow executed in a decidedly non-American way. Good food for working hard. Most of the young guys manage to inhale enough food to feed a small village in less than 15 minutes and then split. I have not yet developed this skill.

Breakfast is at 6:00. While this seems unreasonably early, predawn is the only time of day when it’s not oppressively hot and humid, so early morning is actually the most productive time around here. Until we get a full time cook, breakfast is being handled by one of the Station hands, a large, strong man, aptly called Bull. The meal is a condensed version of the English fry, meaning fried eggs, grilled tomatoes, Canadian-ish bacon, and toast. Every once in a while spaghetti-on-toast makes an appearance. (It’s basically spaghetti-O’s on toast. Yuck.) There are other strange Australian breakfast habits, like baked beans on toast, or pancakes with ice cream and syrup. (I had this particular delicacy at the HiWay Inn. What a GREAT idea!) All of this is accompanied by hot tea, coffee or milo (“energy food drink” something like tasteless hot chocolate, if you can bear to drink anything hot.

The next meal of the day is called “Smoko,” which I believe is a derivative of the smoking break. It is every morning at 9:30 and is recognized as being every bit as legitimate a meal as any other. It usually involves a cup of tea or coffee and whatever baked good Kay came up with the day before. America, I think there is something to be learned here.

Lunch is from 12:30-1:30; a difficult adjustment when you expect it at noon on the dot. Kay puts out sandwich fixings, salad (no dressing, only mayo – very Belg), leftovers from last night, and something new each day.

Work generally wraps up around 5 (thus far) and then at 6:00 the Recreational Club opens. The Rec Club is a little concrete structure with a pool table, a flat screen, a bar and a back patio. Drinks can only be bought from 6-7 and no alcohol leaves the building. There are 2 well-stocked fridges full of sodas (which all seem to be referred to as “Cokes”), beer, and canned mixed drinks (which are only available on Fri & Sat). Only 1 brand of beer is carried; XXXX Gold and XXXX Bitter, a Queensland company, both varieties of which are terrible concoctions that the guys swear by. There is also an unusual assortment of chips and candy bars, including “Twisties,” “Freddo Frog Twins,” “Crunchies,” and “Raspberry Gummies.” My favorite aspect of Australian food is that instead of listing “calories” on the nutritional label, it informs you of the “energy” content – a far more positive spin on junk food.

Last but certainly never least, dinner starts at 7:00. Wow. We have had roast chicken, curry beef with rice, roast with squash, onions and potatoes, and best of all, meat pies, to name just a few. Everything is something very familiar, yet somehow executed in a decidedly non-American way. Good food for working hard. Most of the young guys manage to inhale enough food to feed a small village in less than 15 minutes and then split. I have not yet developed this skill.

Critters

Australia during the Wet is so much more beautiful than I had expected. It is a world of bright blue skies with puffy white cloudy and green grass standing knee high literally as far as the eye can see. I have experienced a fair bit of America’s “big sky country,” but this takes it to a whole new scale. The landscape alternates between gum tree brush and wide open pasture, flat and green forever.

With the rain all the flowers are in bloom on bushes, in trees, and tucked into the grass. I haven’t learned many of the plants yet. Even the grass is different here.

The critters, however, are absolutely my favorite part of this fairly absurd place, and I am working to learn them all. There are birds EVERYWHERE. Outside the kitchen there are crows that sound like baby sheep and something else that sounds like a child practicing the recorder. I’m not sure what those are yet. Driving down the highway or checking water holes (called “turkey nests”) are the best places to find fowl. There are bush turkeys, which look like large, fat roadrunners, and magpie geese, which look like geese dressed in magpie outfits. A few days ago I got to see a fledgling wedge tailed hawk, which I’m told is the largest predatory bird in Australia. This one was average eagle size, but apparently they get much bigger. There are also gallahs which look like small parrots with like grey backs and magenta pink bellies. When they fly they sort of hunch forward and hurl themselves around. It’s a wonder to me that they get airborne at all.

There are also reptiles; snakes and skinks and lime green frogs and big warty cane toads. The first time I saw a cane toad I could have sworn it was the size of a cat, but now that I’ve seen more I suppose surprise was exaggerating my perception. They are huge though, by toad standards. They come out at dusk and like to sit in the puddles of light thrown by the street lights and the kitchen windows. They sit very still and with very straight backs, looking like little sentries or something out of a Miasaki film. You can walk straight up to them and they don’t budge an inch, they just stare right through you. It’s a little creepy.

Of course Australia wouldn’t be Australia is there weren’t kangaroos. And boy are there! They seem to exist here the way we have rabbits at home. They don’t do much except for eat and hop around. They’re REALLY cool when they move though. They lean awkwardly forward when they move but still manage grace and agility. Contrary to American popular belief, folks here don’t hate kangaroos. They mostly seem indifferent to them until one hops in front of their Toyota. They do shoot them, but you need tags, so it’s more like deer hunting in the US.

One critter I haven’t yet seen is a Brumby. Brumbies are the Australian equivalent to the mustang and apparently there are hundreds (thousands?) of them on the station. Unlike those in ‘Man from Snowy River’, they seem to keep to themselves and don’t cause much trouble. Even the most hardened old timer will admit that they are beautiful horses and really cool to see out in the paddocks.

Also, while there are crocodiles in Australia, there aren’t any (many?) in the Northern Territory. So no crocodile Dundee-ing for me.

With the rain all the flowers are in bloom on bushes, in trees, and tucked into the grass. I haven’t learned many of the plants yet. Even the grass is different here.

The critters, however, are absolutely my favorite part of this fairly absurd place, and I am working to learn them all. There are birds EVERYWHERE. Outside the kitchen there are crows that sound like baby sheep and something else that sounds like a child practicing the recorder. I’m not sure what those are yet. Driving down the highway or checking water holes (called “turkey nests”) are the best places to find fowl. There are bush turkeys, which look like large, fat roadrunners, and magpie geese, which look like geese dressed in magpie outfits. A few days ago I got to see a fledgling wedge tailed hawk, which I’m told is the largest predatory bird in Australia. This one was average eagle size, but apparently they get much bigger. There are also gallahs which look like small parrots with like grey backs and magenta pink bellies. When they fly they sort of hunch forward and hurl themselves around. It’s a wonder to me that they get airborne at all.

There are also reptiles; snakes and skinks and lime green frogs and big warty cane toads. The first time I saw a cane toad I could have sworn it was the size of a cat, but now that I’ve seen more I suppose surprise was exaggerating my perception. They are huge though, by toad standards. They come out at dusk and like to sit in the puddles of light thrown by the street lights and the kitchen windows. They sit very still and with very straight backs, looking like little sentries or something out of a Miasaki film. You can walk straight up to them and they don’t budge an inch, they just stare right through you. It’s a little creepy.

Of course Australia wouldn’t be Australia is there weren’t kangaroos. And boy are there! They seem to exist here the way we have rabbits at home. They don’t do much except for eat and hop around. They’re REALLY cool when they move though. They lean awkwardly forward when they move but still manage grace and agility. Contrary to American popular belief, folks here don’t hate kangaroos. They mostly seem indifferent to them until one hops in front of their Toyota. They do shoot them, but you need tags, so it’s more like deer hunting in the US.

One critter I haven’t yet seen is a Brumby. Brumbies are the Australian equivalent to the mustang and apparently there are hundreds (thousands?) of them on the station. Unlike those in ‘Man from Snowy River’, they seem to keep to themselves and don’t cause much trouble. Even the most hardened old timer will admit that they are beautiful horses and really cool to see out in the paddocks.

Also, while there are crocodiles in Australia, there aren’t any (many?) in the Northern Territory. So no crocodile Dundee-ing for me.

Daily life in the Back of Beyond

There are many facets to normal life the one doesn't usually consider that here, cut off from 'civilization', suddenly become a challenge rather than a nuance to everyday life. As my boss Cameron put it, "When you live out in the bush, no one's going to come help you, so you have to do it all yourself." Already I have played the roll of plumber, electrician, gardener, and more, because we are simply too far to pay for such services.

Other aspects of life require creative solutions as well. Since the nearest town is over 5 hours away, grocery shopping is fairly impractical. Thus once a week on Tuesdays, a gigantic refrigerated truck comes to the station to deliver food and supplies that the station manager has ordered in advance. This same truck stops at every station along the road making deliveries before returning to Mount Isa, some 8ish hours away. On Fridays the mail plane comes, swooping down to swap incoming mail for outgoing, and taking off again for the next station. While this is a vast improvement from the mail wagons of the early 20th century, which would come something like once every 6 weeks or, in some places, once every 6 months, it is still vastly different for someone who is accustomed to the option of overnight delivery.

Garbage is another issue. What do you do with your rubbish when you are too far away to have it picked up? The answer - you burn it. The first time I burned my trash, my urbanized, modernized, liberalized conscience revolted. But given the circumstances, what else are you going to do?

Electricity and water are also not standard order out here the way they are at home. There is a shed, about the size of a 2 car garage that house the generator. It rumbles along all day and all night powering the station. That means that there is never silence around the homestead, but also that my wonderful air conditioner ("air con") is kept cranking at all times. God bless air cons.

Water is supplied through 2 sources- rain water and ground water. Surprisingly enough, the rain water is for drinking, while the ground water is for washing and watering the livestock. The rain water is collected from roof runoff in gigantic cisterns during the Wet. Since no one has said anything, I imagine this lasts through the Dry. Heaven forbid it should run out. The ground water is piped up from artesian wells using what is called a "bore"- once wind operated, now diesel. It is laden with minerals and is terrible to drink, although I've heard that after a few days out mustering, you learn to be less picky.

Other aspects of life require creative solutions as well. Since the nearest town is over 5 hours away, grocery shopping is fairly impractical. Thus once a week on Tuesdays, a gigantic refrigerated truck comes to the station to deliver food and supplies that the station manager has ordered in advance. This same truck stops at every station along the road making deliveries before returning to Mount Isa, some 8ish hours away. On Fridays the mail plane comes, swooping down to swap incoming mail for outgoing, and taking off again for the next station. While this is a vast improvement from the mail wagons of the early 20th century, which would come something like once every 6 weeks or, in some places, once every 6 months, it is still vastly different for someone who is accustomed to the option of overnight delivery.

Garbage is another issue. What do you do with your rubbish when you are too far away to have it picked up? The answer - you burn it. The first time I burned my trash, my urbanized, modernized, liberalized conscience revolted. But given the circumstances, what else are you going to do?

Electricity and water are also not standard order out here the way they are at home. There is a shed, about the size of a 2 car garage that house the generator. It rumbles along all day and all night powering the station. That means that there is never silence around the homestead, but also that my wonderful air conditioner ("air con") is kept cranking at all times. God bless air cons.

Water is supplied through 2 sources- rain water and ground water. Surprisingly enough, the rain water is for drinking, while the ground water is for washing and watering the livestock. The rain water is collected from roof runoff in gigantic cisterns during the Wet. Since no one has said anything, I imagine this lasts through the Dry. Heaven forbid it should run out. The ground water is piped up from artesian wells using what is called a "bore"- once wind operated, now diesel. It is laden with minerals and is terrible to drink, although I've heard that after a few days out mustering, you learn to be less picky.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)